With the introduction of Windows 10, Microsoft has proven that it is committed to improving its products to meet users' demands. Windows 10 is available for upgrading from earlier versions of Windows 7/8/8.1. After upgrading to Windows 10, you may need the Product Key to activate your Windows 10. If you are looking to enjoy the full features of Windows 10, we will be exploring various ways to activate your Windows 10 and also provide you with Generic Windows 10 Product keys. These keys work for all versions of Windows and can be used for free.

1. Is it Possible to Get Free Windows 10 Product Key

2. Find Windows 10 Free Key on Computer

3. Get Windows 10 License Key from Inside Windows

4. How to Activate Windows 10 with Product Key for Free

5. How to Activated Windows 10 Without Product Key

6. Forgot Windows 10 Password? How to Recover Windows 10 Password

1. Is It Possible to Get Free Windows 10 Product Key

This is the question that a lot of users ask. Although the free upgrade to Windows 10 is ended in 2016 on the 16th of July, but you can still download Windows 10 unofficially and upgrade to the free version.

List of Windows 10 Product Key

Here is a list of Windows 10 product keys. These product keys are useful for those who don't get the Windows copy.

| Windows 10 Product Keys List Free Download: | DPH2V-TTNVB-4X9Q3-TJR4H-KHJW4 |

| W269N-WFGWX-YVC9B-4J6C9-T83GX | |

| MH37W-N47XK-V7XM9-C7227-GCQG9 | |

| TX9XD-98N7V-6WMQ6-BX7FG-H8Q99 | |

| WNMTR-4C88C-JK8YV-HQ7T2-76DF9 | |

| W269N-WFGWX-YVC9B-4J6C9-T83GX |

List of Windows Server 2016 All Versions Product Key

| Windows Server 2016 Datacenter Key | CB7KF-BWN84-R7R2Y-793K2-8XDDG |

| Windows Server 2016 Standard Key | WC2BQ-8NRM3-FDDYY-2BFGV-KHKQY |

| Windows Server 2016 Essentials Key | JCKRF-N37P4-C2D82-9YXRT-4M63B |

List of Windows 10 Product Keys for All Versions

| Windows 10 Professional Key | W269N-WFGWX-YVC9B-4J6C9-T83GX |

| Windows 10 Professional N Product Key | MH37W-N47XK-V7XM9-C7227-GCQG9 |

| Windows 10 Enterprise Key | NPPR9-FWDCX-D2C8J-H872K-2YT43 |

| Windows 10 Enterprise N Key | DPH2V-TTNVB-4X9Q3-TJR4H-KHJW4 |

| Windows 10 Education Key | NW6C2-QMPVW-D7KKK-3GKT6-VCFB2 |

| Windows 10 Home N | AKJUS-WY2CT-JWBJ2-T68TQ-YBH2V |

| Windows 10 Enterprise 2015 LTSB N | JAHSU-QMPVW-D7KKK-3GKT6-VCFB2 |

| Windows 10 Pro for Workstations | AKSIU-WY2CT-JWBJ2-T68TQ-YBH2V |

| Windows Pro N for Workstations | SJUY7-NFMTC-H88MJ-PFHPY-QJ4BJ |

| Windows 10 Pro Education | AJUYS-8C467-V2W6J-TX4WX-WT2RQ |

| Windows 10 Enterprise N | AJSU7-GRT3P-VKWWX-X7T3R-8B639 |

| Windows 10 Enterprise Key | ALSOI-MHBT6-FXBX8-QWJK7-DRR8H |

| Windows 10 Enterprise S | 8UY76-TNFGY-69QQF-B8YKP-D69TJ |

| Windows 10 Enterprise G N | AJSUY-NPHTM-C97JM-9MPGT-3V66T |

| Windows 10 Pro Education N | ALSOI-4C88C-JK8YV-HQ7T2-76DF9 |

List of Windows 10 Activation Keys

| Windows Server 2016 Standard | WC2BQ-8NRM3-FDDYY-2BFGV-KHKQY |

| Windows Server 2016 Essentials | JCKRF-N37P4-C2D82-9YXRT-4M63B |

| Windows 10 Professional | W269N-WFGWX-YVC9B-4J6C9-T83GX |

| Windows 10 Professional N | MH37W-N47XK-V7XM9-C7227-GCQG9 |

| Windows 10 Enterprise | NPPR9-FWDCX-D2C8J-H872K-2YT43 |

| Windows 10 Enterprise N | DPH2V-TTNVB-4X9Q3-TJR4H-KHJW4 |

| Windows 10 Education | NW6C2-QMPVW-D7KKK-3GKT6-VCFB2 |

| Windows 10 Education N | 2WH4N-8QGBV-H22JP-CT43Q-MDWWJ |

2. Find Windows 10 Free Key on Computer

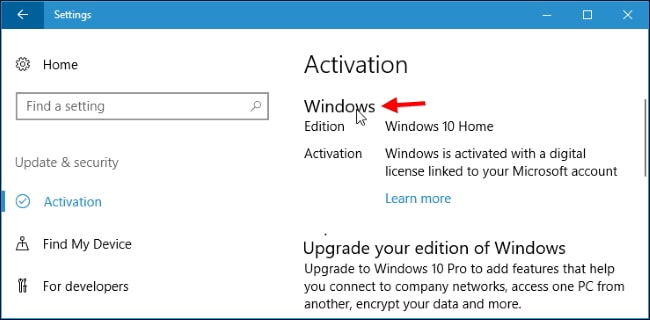

When you navigate to the "Settings" on your Windows, you will find a page where your activation information can be found. Your key will not display here though. To find this page, go to "Settings", click on "Update & Security" and then "Activation".

On the activation page, if you have a digital license, you will see the message of "Windows is activated with a digital license". If you have a Microsoft account, you can link it to your license by clicking on "add a Microsoft Account" at the bottom of the page and then log into your Microsoft account. If you still cannot find your product key, just take advantage of free product key finder to help you, here we list Top 10 Product Key Finder for Totally Free.

3. Get Windows 10 License Key from Inside Windows

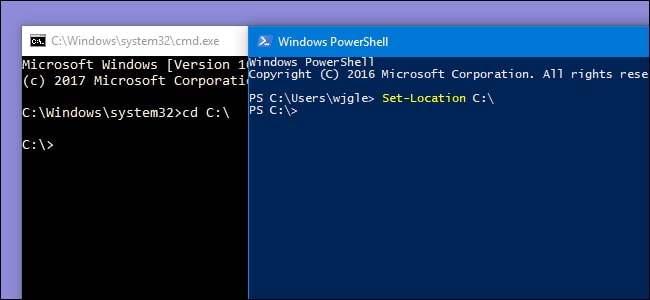

To display the OEM key embedded in your System's BIOS/UEFI, enter the following lines into the PowerShell or admin command.

wmic path softwarelicensingservice get OA3xOriginalProductKey or powershell "(Get-WmiObject -query 'select * from SoftwareLicensingService').OA3xOriginalProductKey"

You can also use a Visual Basic Script to retrieve registry-based Windows Keys. You can download the script, copy the text into your notepad, save it as a .vbs file and double click it to run the file.

4. How to Activate Windows 10 with Product Key for Free

Step 1. After you have turned on your computer, navigate to settings or press Windows Key + I on the keyboard.

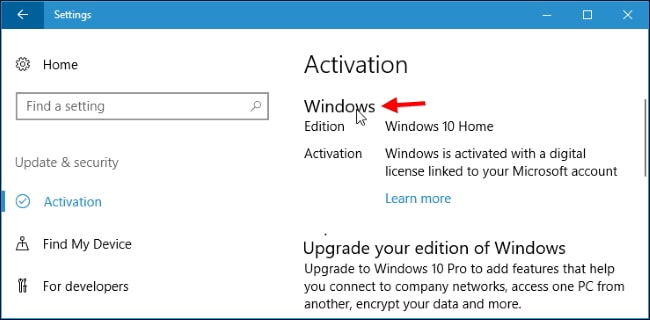

Step 2. Click on "Update and Security". Select "Activation" from the left-side menu.

Step 3. If you do not have a Windows License Key, you can visit the Microsoft store by clicking on "Go to Store". Windows will open the product page for Windows 10. You can purchase the Windows key and use the key to activate your version of Windows 10.

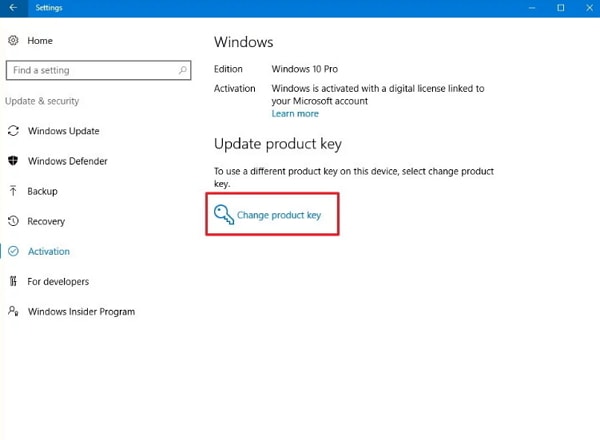

Step 4. Navigate back to Settings. Click on "Update and Security", then tap on "Activation" and "Change Product Key" option.

Step 5. Enter your product key. Windows will verify the product key over the internet and activate your Windows 10.

5. How to Activate Windows 10 Without Product Key

You can also activate your Windows 10 without using product key by following the steps below.

-

Open Run and Type "SLUI".

-

Open the coding windows.

-

Copy the code that shows up.

-

Enter the code and press "Enter".

-

Your Windows will activate afterwards.

-

Restart your computer.

6. Forgot Windows 10 Password? How to Recover Windows 10 Password

While you are trying to get a product key for your Windows 10, it is possible that you may lose your windows 10 password. If this happens, you can recover forgotten or lost Windows 10 password using a third-party tool that has been tested and proven to be effective. What we introduce to you is Passper WinSenior, which is capable of resetting your forgotten password on your Windows 10 computer without losing data. Follow the steps below to recover Windows 10 password.

High Recovery Rate: Recover all Windows password with super high recovery rate.

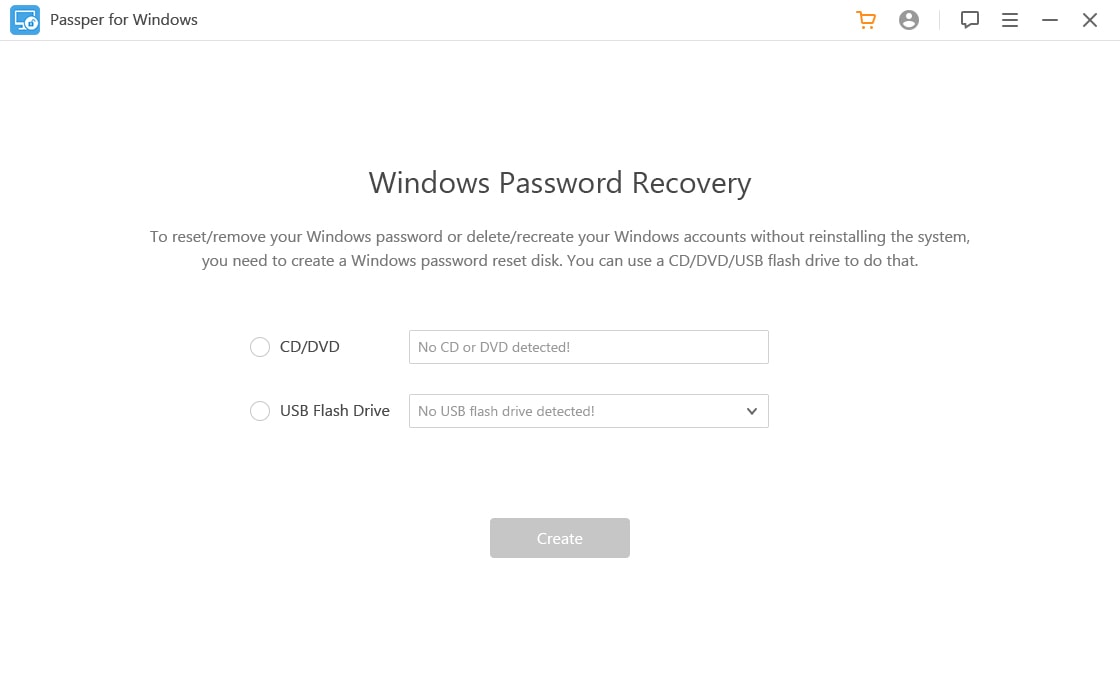

Create Password Reset Disk with 2 Options: Both the DVD/CD and USB flash drive can be used to burn a Windows password reset disk in one click.

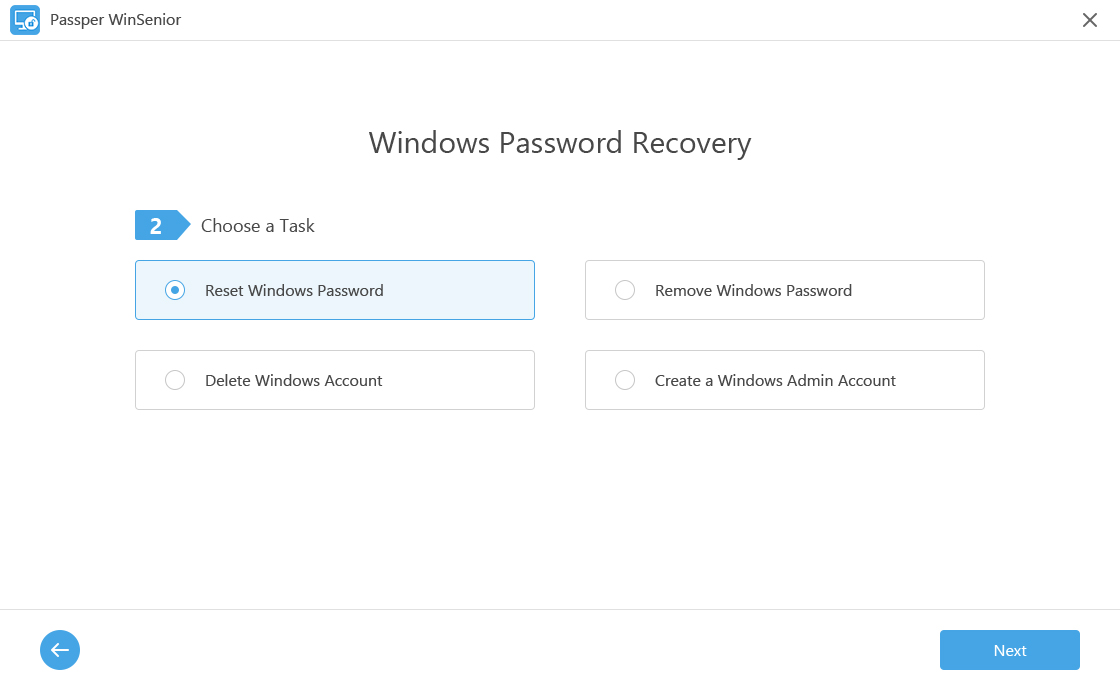

4 Password Recovery Solutions: A comprehensive solution is provided allowing you to reset, remove, delete or create the Windows password.

Recover in 3 Simple Steps: You can find the lost Windows login password and unlock your computer within 3 steps.

50+ Computer Brands are Supported: All Windows computer, laptops and tablets are supported, such as Dell, HP, Lenovo, Samsung, Toshiba, ThinkPad, IBM, Sony, Acer, ASUS, etc.

100,000 + Downloads

Step 1. Download and install Passper WinSenior on another computer that you have access to. Then insert USB flash drive or external CD or DVD to burn a bootable disk.

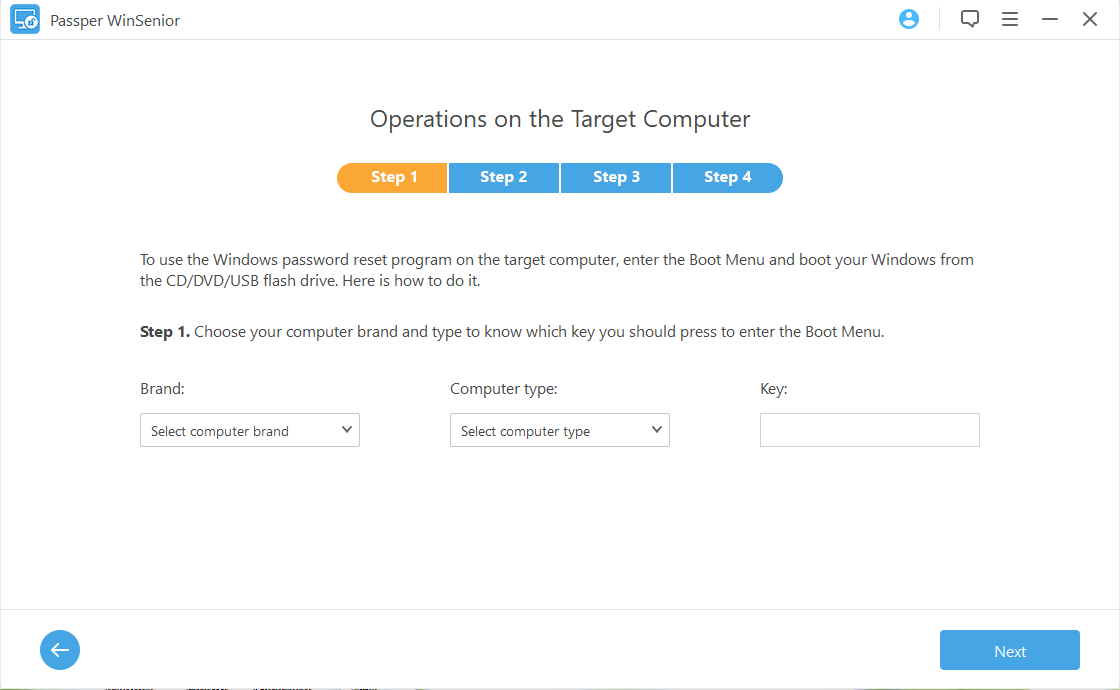

Step 2. After you have successfully created the bootable drive, connect the drive to your locked computer. Start up your PC and you will be prompted to enter the computer into Boot Menu.

Step 3. Once your PC boots correctly, The Passper WinSenior interface will come up. On this interface, you can either remove or reset your password. You also have the option to remove the admin account or create an entirely new one.

Conclusion

If you still have the old versions of Windows on your computer, it is time for you to make a change. Upgrading to Windows 10 is a great change, and there are lots of features you can enjoy after the upgrade process. If, when you upgrade your Windows version, you forget the password to your Windows, get Passper WinSenior to recover your Windows password now.